Ballycotton Cliff Walk

Ballycotton Cliff Walk

Welcome to The Ballycotton Cliff Walk, Ballycotton is a fishing village, so no better place to enjoy a fresh seafood meal before visiting its cliff walk, and admire its Lighthouse which stand on a nearby island. This Lighthouse was built mid-1800s with a black tower one of two in Ireland. After a steamship the Sirius became a shipwreck the Lighthouse was commissioned to help navigate this treacherous stretch of water. The Lighthouse is automated but it’s possible to visit as Ballycotton Sea Adventures operate boat tours to the island.

Welcome to The Ballycotton Cliff Walk, Ballycotton is a fishing village, so no better place to enjoy a fresh seafood meal before visiting its cliff walk, and admire its Lighthouse which stand on a nearby island. This Lighthouse was built mid-1800s with a black tower one of two in Ireland. After a steamship the Sirius became a shipwreck the Lighthouse was commissioned to help navigate this treacherous stretch of water. The Lighthouse is automated but it’s possible to visit as Ballycotton Sea Adventures operate boat tours to the island.

Ballycotton Cliff Walk is lovely but avoid if wet because trail gets very slippery and muddy and can be unpleasant.

Ballycotton Cliff Walk is lovely but avoid if wet because trail gets very slippery and muddy and can be unpleasant.

Good foot wear such as hiking boots are recommended as the narrow path can get spongey and slippery especially after long spells of rain. We walked for an hour to a distant headland where wonderful views of the Lighthouse was our reward.

Good foot wear such as hiking boots are recommended as the narrow path can get spongey and slippery especially after long spells of rain. We walked for an hour to a distant headland where wonderful views of the Lighthouse was our reward.

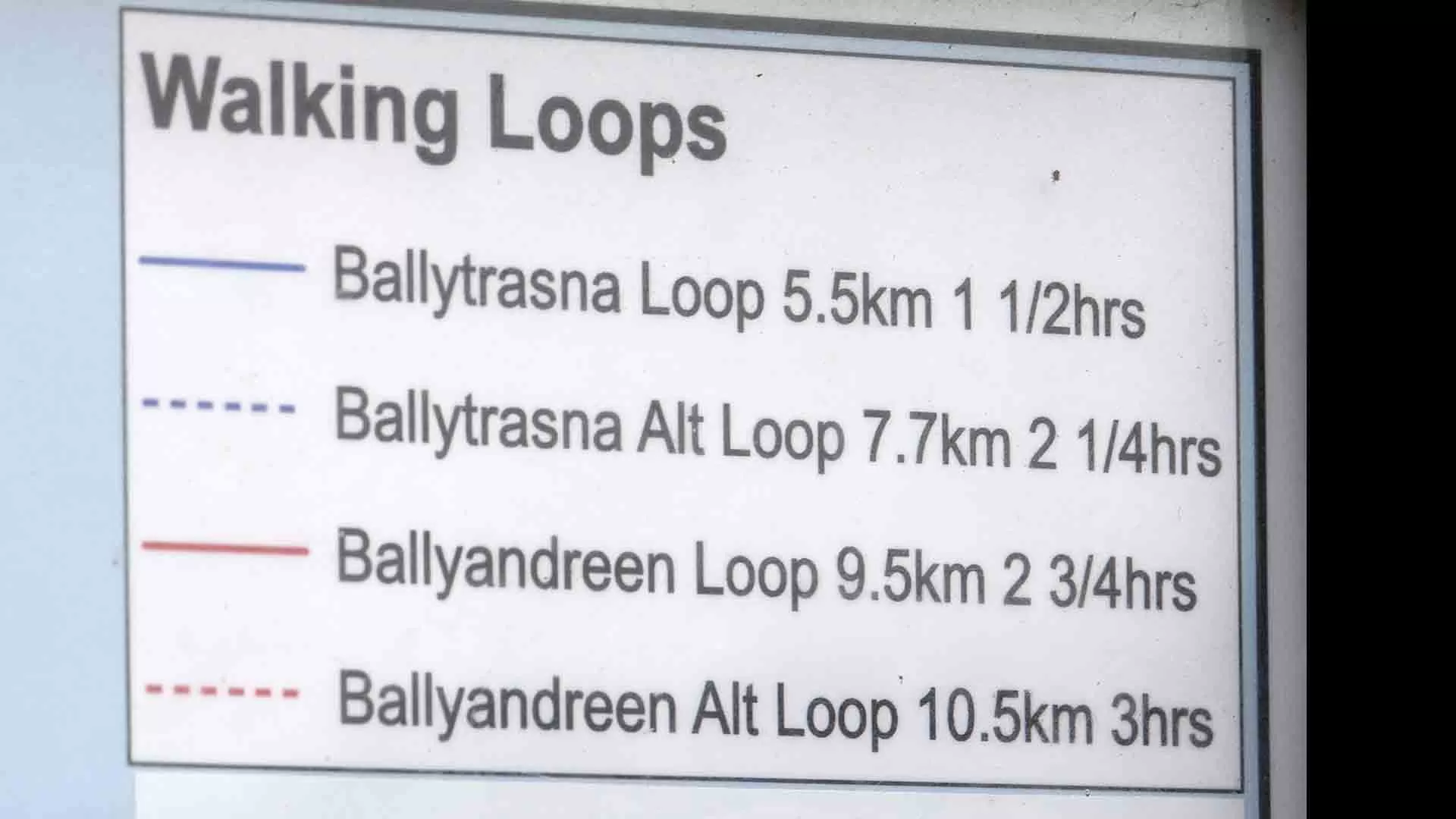

Walking Loops, some take you on public roads (not for me).

Walking Loops, some take you on public roads (not for me).

Ballycotton Lighthouse

Ballycotton Lighthouse

The MV Alta

The MV Alta

This is the MV Alta which ended its journey here against the rocks at Ballandreen Bay, thanks to storm Dennis. The original name of this ship was the Tananger, a merchant ship built in 1976. The Alta suffered engine failure and then abandoned by its crew. The Royal Navy spotted it in the Atlantic where it drifted for 18 months and covered over 2,300 lonely nautical miles, before appearing off the Irish coast. The ghost ship was pushed onto the rocks making it possible to view the Alta wreck from the Ballycotton Cliff Walk.

The Irish government was left responsible for this wreck as no owner came forward. The wreck was scavenged and also became a major attraction, but locals were less impressed with this influx of people because of damage to farmland and property let alone dealing with the hazardous material aboard the forsaken ship. Many winter storms have now broken the Alta into many parts and it still remains a hazard to this day, making the Sea responsible for its disposal.

This is the MV Alta which ended its journey here against the rocks at Ballandreen Bay, thanks to storm Dennis. The original name of this ship was the Tananger, a merchant ship built in 1976. The Alta suffered engine failure and then abandoned by its crew. The Royal Navy spotted it in the Atlantic where it drifted for 18 months and covered over 2,300 lonely nautical miles, before appearing off the Irish coast. The ghost ship was pushed onto the rocks making it possible to view the Alta wreck from the Ballycotton Cliff Walk.

The Irish government was left responsible for this wreck as no owner came forward. The wreck was scavenged and also became a major attraction, but locals were less impressed with this influx of people because of damage to farmland and property let alone dealing with the hazardous material aboard the forsaken ship. Many winter storms have now broken the Alta into many parts and it still remains a hazard to this day, making the Sea responsible for its disposal.

R.N.L.B. Mary Stafford

R.N.L.B. Mary Stafford

Local History

Local History

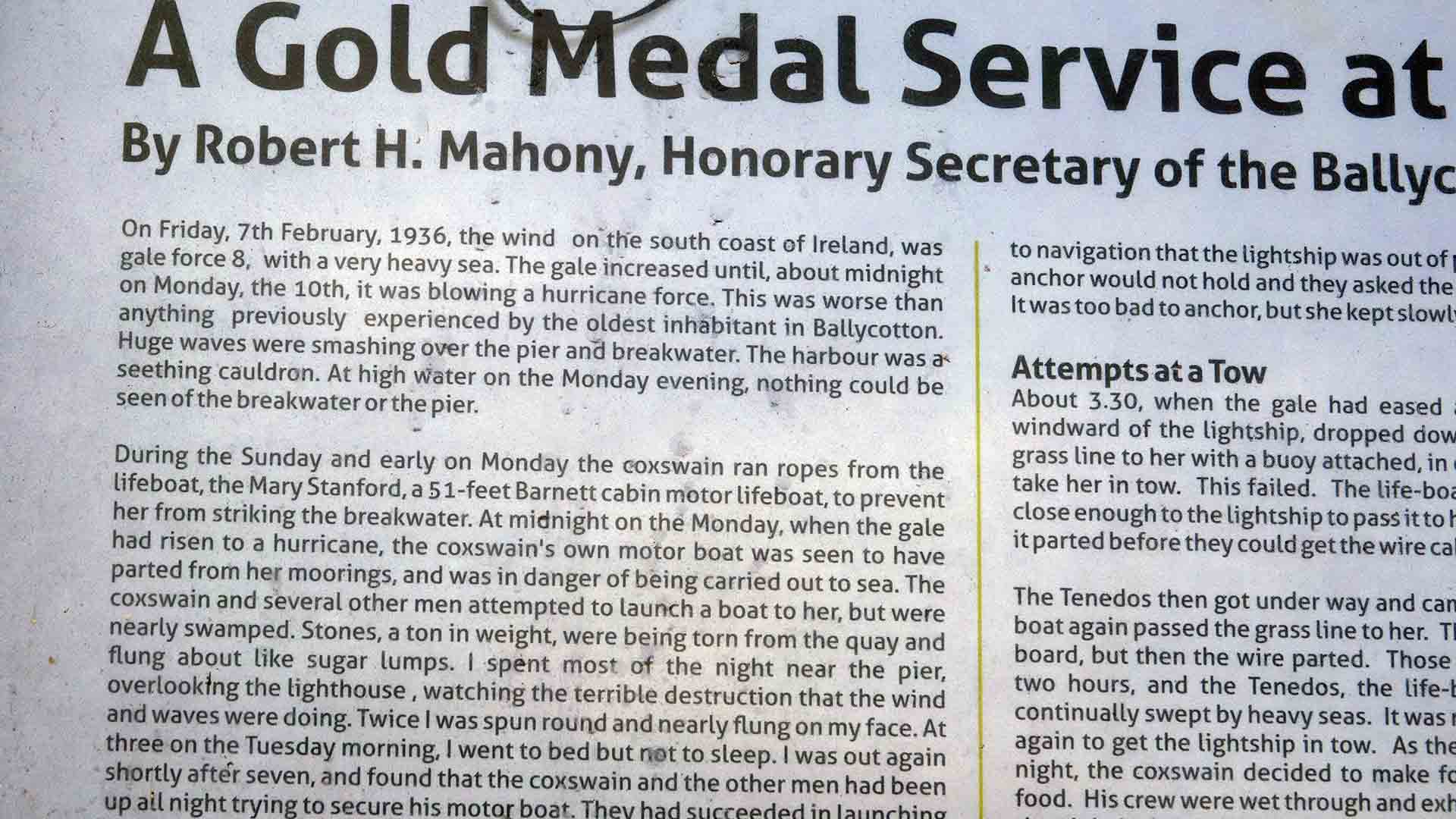

A Gold Medal Service at Ballycotton: February 1936

A Gold Medal Service at Ballycotton: February 1936

A Gold Medal Service at Ballycotton: February 1936

By Robert H. Mahony, Honorary Secretary of the Ballycotton Station

By Robert H. Mahony, Honorary Secretary of the Ballycotton Station

From Above

On Friday,7th February, 1936, the wind on the south coast of Ireland, was gale force 8, with a very heavy sea. The gale increased until, about midnight on Monday, the 10th, it was blowing a hurricane force. This was worse than anything previously experienced by the oldest inhabitant in Ballycotton. Huge waves were smashing over the pier and breakwater. The harbour was a seething cauldron. at high water on the Monday evening, nothing could be seen of the breakwater or the pier

During the Sunday and early on Monday the coxswain ran ropes from the lifeboat, the Mary Stanford, a51-feet Barnett cabin motor lifeboat, to prevent her from striking the breakwater. At midnight on the Monday, when the gale had risen to a hurricane, the coxswain’s own boat was seen to have parted from her moorings, and was in danger of being carried out to sea. The coxswain and several other men attempted to launch a boat to her. but were nearly swamped. Stones, a ton in weight, were torn from the quay and flung about like sugar lumps. I spent most of the night near the pier, overlooking the lighthouse, watching the terrible destruction that the wind and waves were doing. Twice I was spun round and nearly flung on my face. At three on the Tuesday morning, I went to bed but not to sleep. I was out again shortly after seven, and found that the coxswain and the other men had been up all night trying to secure his motor boat. They had succeeded in launching a boat, got a rope to the motor boat and secured her. It was at that moment, after this long night of anxiety, that the call for the life-boat came.

From Above

On Friday,7th February, 1936, the wind on the south coast of Ireland, was gale force 8, with a very heavy sea. The gale increased until, about midnight on Monday, the 10th, it was blowing a hurricane force. This was worse than anything previously experienced by the oldest inhabitant in Ballycotton. Huge waves were smashing over the pier and breakwater. The harbour was a seething cauldron. at high water on the Monday evening, nothing could be seen of the breakwater or the pier

During the Sunday and early on Monday the coxswain ran ropes from the lifeboat, the Mary Stanford, a51-feet Barnett cabin motor lifeboat, to prevent her from striking the breakwater. At midnight on the Monday, when the gale had risen to a hurricane, the coxswain’s own boat was seen to have parted from her moorings, and was in danger of being carried out to sea. The coxswain and several other men attempted to launch a boat to her. but were nearly swamped. Stones, a ton in weight, were torn from the quay and flung about like sugar lumps. I spent most of the night near the pier, overlooking the lighthouse, watching the terrible destruction that the wind and waves were doing. Twice I was spun round and nearly flung on my face. At three on the Tuesday morning, I went to bed but not to sleep. I was out again shortly after seven, and found that the coxswain and the other men had been up all night trying to secure his motor boat. They had succeeded in launching a boat, got a rope to the motor boat and secured her. It was at that moment, after this long night of anxiety, that the call for the life-boat came.

Telephone Lines Down

Telephone Lines Down

The men were just back, at eight o’clock, when the Civil Guard at Ballycotton rang me up. A messenger had arrived (all telephone communication except by the local lines had broken down twenty-four hours before) with a message that the Daunt Rock Lightship, with eight men; had broken from her moorings twelve miles away, and was drifting towards Ballycotton.

I gave the coxswain the message and he made no reply. I had seen the weather. Seas were breaking over the boathouse, where the boarding boat was kept. I did not believe it possible for the coxswain even to get aboard the life-boat at her moorings. I was afraid to order him out.

The men were just back, at eight o’clock, when the Civil Guard at Ballycotton rang me up. A messenger had arrived (all telephone communication except by the local lines had broken down twenty-four hours before) with a message that the Daunt Rock Lightship, with eight men; had broken from her moorings twelve miles away, and was drifting towards Ballycotton.

I gave the coxswain the message and he made no reply. I had seen the weather. Seas were breaking over the boathouse, where the boarding boat was kept. I did not believe it possible for the coxswain even to get aboard the life-boat at her moorings. I was afraid to order him out.

He left and went down to the harbour. I followed a little later. To my amazement, the life-boat was already at the harbour mouth, dashing out between the piers. The coxswain had not waited for orders. His crew were already at the harbour. He had not fired the maroons for he did not want to alarm the village. Without a word they had slipped away. As I watched the life-boat I thought every minute she must turn back. At one moment a sea crashed on her; at the next she was standing on her heel. But she went on. The people who were watching her left the church to go the church to pray. I watched her till she was a mile off, at the lighthouse, where she met seas so mountainous that her spray, as we could see (and the lighthouse keeper verified it), was flying over the lantern 196 feet high. At the lighthouse, the life-boat seemed to hesitate. She turned around. We thought she was coming back. Then, to our horror, the coxswain took her through the sound between the two islands. That way, as we knew, it was much more dangerous than the open sea, and would save half a mile.

He left and went down to the harbour. I followed a little later. To my amazement, the life-boat was already at the harbour mouth, dashing out between the piers. The coxswain had not waited for orders. His crew were already at the harbour. He had not fired the maroons for he did not want to alarm the village. Without a word they had slipped away. As I watched the life-boat I thought every minute she must turn back. At one moment a sea crashed on her; at the next she was standing on her heel. But she went on. The people who were watching her left the church to go the church to pray. I watched her till she was a mile off, at the lighthouse, where she met seas so mountainous that her spray, as we could see (and the lighthouse keeper verified it), was flying over the lantern 196 feet high. At the lighthouse, the life-boat seemed to hesitate. She turned around. We thought she was coming back. Then, to our horror, the coxswain took her through the sound between the two islands. That way, as we knew, it was much more dangerous than the open sea, and would save half a mile.

Tremendous Seas

Tremendous Seas

He took her through the sound, after consulting with his second-coxswain, and there, so he told me afterwards, the seas were tremendous. The life-boat came off the one sea and dropped into the engines had gone through the bottom of the boat, but the motor mechanic reported “All’s well. After that, she will go through anything. “ The coxswain now had the whole crew in the after cockpit. After each sea had filled it, he counted his men.

He drove the life-boat safely through the sound, and then had a run before the wind along the coast. When the life-boat was off Ballycroneen, about six miles from Ballycotton, the following seas got worse, and the coxswain decided to put out his drogue to steady the life-boat. He eased the engine to do it, and several seas struck him on the head, half-stunning him. Then, as the drogue was being put out, an extra heavy curling sea came over the port quarter. It filled the cockpit. It knocked down every man on board. When they had recovered, they found that the drogue-ropes had folded, but the drogue was drawing.

The life-boat ran on towards the shore, but in the spray and rain and sleet, the shore was not visible and nothing of the lightship could be seen. The coxswain then decided to make for the usual position of the lightship, and put the life-boat’s head to the sea. He went on for several miles, until he came to what he thought her position had been, but owing to the erratic course he had taken, and in the rain and sleet, he could not be sure. There was still no sign of her, and he decided to run for Queentown for information. He reached it at eleven in the morning after a trying time, for he had now no drogue to steady the life-boat in the breaking seas in the mouth of the harbour, and used his oil-sprays to calm the breakwaters a little.

At Queenstown, he got the exact position of the lightship from the pilots; tried to telephone me at Ballycotton, but found that the wires were still down; and put to sea again at once. Just after midday he found the lightship. She had got an anchor down and was a quarter of a mile south-west of the Daunt Rock and half a mile from the shore. H.M. Destroyer Tenedos and the S.S. Innisfallen were standing by her. When the life-boat arrived the Innisfallen left.

The coxswain spoke to the crew of the light vessel. He found that they did not want to leave her, for they knew the danger it was to navigation that the lightship was out of position. But they feared that their anchor would not hold and they asked the life-boat to stand by. This she did. It was too bad to anchor, but she kept slowly steaming and drifting.

He took her through the sound, after consulting with his second-coxswain, and there, so he told me afterwards, the seas were tremendous. The life-boat came off the one sea and dropped into the engines had gone through the bottom of the boat, but the motor mechanic reported “All’s well. After that, she will go through anything. “ The coxswain now had the whole crew in the after cockpit. After each sea had filled it, he counted his men.

He drove the life-boat safely through the sound, and then had a run before the wind along the coast. When the life-boat was off Ballycroneen, about six miles from Ballycotton, the following seas got worse, and the coxswain decided to put out his drogue to steady the life-boat. He eased the engine to do it, and several seas struck him on the head, half-stunning him. Then, as the drogue was being put out, an extra heavy curling sea came over the port quarter. It filled the cockpit. It knocked down every man on board. When they had recovered, they found that the drogue-ropes had folded, but the drogue was drawing.

The life-boat ran on towards the shore, but in the spray and rain and sleet, the shore was not visible and nothing of the lightship could be seen. The coxswain then decided to make for the usual position of the lightship, and put the life-boat’s head to the sea. He went on for several miles, until he came to what he thought her position had been, but owing to the erratic course he had taken, and in the rain and sleet, he could not be sure. There was still no sign of her, and he decided to run for Queentown for information. He reached it at eleven in the morning after a trying time, for he had now no drogue to steady the life-boat in the breaking seas in the mouth of the harbour, and used his oil-sprays to calm the breakwaters a little.

At Queenstown, he got the exact position of the lightship from the pilots; tried to telephone me at Ballycotton, but found that the wires were still down; and put to sea again at once. Just after midday he found the lightship. She had got an anchor down and was a quarter of a mile south-west of the Daunt Rock and half a mile from the shore. H.M. Destroyer Tenedos and the S.S. Innisfallen were standing by her. When the life-boat arrived the Innisfallen left.

The coxswain spoke to the crew of the light vessel. He found that they did not want to leave her, for they knew the danger it was to navigation that the lightship was out of position. But they feared that their anchor would not hold and they asked the life-boat to stand by. This she did. It was too bad to anchor, but she kept slowly steaming and drifting.

Attempts at a Tow

Attempts at a Tow

About 3.30, when the gale had eased a little, the Tenedos anchored to windward of the lightship, dropped down towards her and tried to float a grass line to her with a buoy attached, in order to get a wire cable to her and take her in tow. This failed. The life-boat then picked up the buoy and got close enough to the lightship to pass it to her. Her crew hauled on the line, but it parted before they could get the wire cable attached to it.

The Tenedos then got under way and came closer to the lightship. The life-boat again passed the grass line to her. This time, she got the towing-wire on board, but then the wire parted. Those attempts had already taken nearly two hours, and the Tenedos, the life-boat, and the lightship, had been continually swept by heavy seas. It was now dark and impossible to attempt again to get the lightship a tow. As the Tenedos was going to stand by all night, the coxswain decided to make for Queenstown for more ropes and food since the night before and been up all that night trying to save their boats. The life-boat reached Queenstown at 9.30 p.m.

The Storm on Land

If conditions were terrible at sea, they were bad on land. Two hours after the life-boat had put out I had gone by car to Cloyne, seven miles away (a difficult journey, for the road was blocked with fallen trees), hoping to be able to telephone from there, but the lines were down. I went on to Midleton, twelve and a half miles, and there found a message giving me the position of the lightship. Then I tried to reach Roche’s Point, the entrance to Queenstown Harbour, in the hope of getting this information to the life-boat, but the fallen trees made it impossible. Returning to Midleton, I telegraphed to the life-boat stations at Courtmacsherry and Youghal, to tell them that the Ballycotton boat was out, and got through on the telephone to Queenstown. From there I learnt that the life-boat had been in and had put out again.

I had 160 gallons of petrol ready at Ballycotton, but it was impossible to get a motor lorry. I telephoned to Cork to send her eighty gallons, but the driver of the lorry injured his arm. A second driver had to got. There was a delay. As soon as the life-boat had the petrol on board, she set out again. It was then four in the afternoon

About 3.30, when the gale had eased a little, the Tenedos anchored to windward of the lightship, dropped down towards her and tried to float a grass line to her with a buoy attached, in order to get a wire cable to her and take her in tow. This failed. The life-boat then picked up the buoy and got close enough to the lightship to pass it to her. Her crew hauled on the line, but it parted before they could get the wire cable attached to it.

The Tenedos then got under way and came closer to the lightship. The life-boat again passed the grass line to her. This time, she got the towing-wire on board, but then the wire parted. Those attempts had already taken nearly two hours, and the Tenedos, the life-boat, and the lightship, had been continually swept by heavy seas. It was now dark and impossible to attempt again to get the lightship a tow. As the Tenedos was going to stand by all night, the coxswain decided to make for Queenstown for more ropes and food since the night before and been up all that night trying to save their boats. The life-boat reached Queenstown at 9.30 p.m.

The Storm on Land

If conditions were terrible at sea, they were bad on land. Two hours after the life-boat had put out I had gone by car to Cloyne, seven miles away (a difficult journey, for the road was blocked with fallen trees), hoping to be able to telephone from there, but the lines were down. I went on to Midleton, twelve and a half miles, and there found a message giving me the position of the lightship. Then I tried to reach Roche’s Point, the entrance to Queenstown Harbour, in the hope of getting this information to the life-boat, but the fallen trees made it impossible. Returning to Midleton, I telegraphed to the life-boat stations at Courtmacsherry and Youghal, to tell them that the Ballycotton boat was out, and got through on the telephone to Queenstown. From there I learnt that the life-boat had been in and had put out again.

I had 160 gallons of petrol ready at Ballycotton, but it was impossible to get a motor lorry. I telephoned to Cork to send her eighty gallons, but the driver of the lorry injured his arm. A second driver had to got. There was a delay. As soon as the life-boat had the petrol on board, she set out again. It was then four in the afternoon

In Imminent Danger

In Imminent Danger

When the life-boat reached the light vessel again, about dusk, she found that the Isolda had arrived. Her captain told the coxswain that he intended to stand by all night and in the morning would try to take the lightship in tow. But the weather since four o’clock had been getting worse. At eight o’clock a big sea went over the lightship, carrying away the forward of the two red lights which are hoisted by a lightship at bow and stern to show that she is out of position. At 9.30, with the wind and sea still increasing, the the coxswain took the life-boat round the lightship’s stern, with his searchlight playing on her. In its light, he could see her crew, with there lifebelts on, and the seas breaking over them, huddled at the stern. The wind, which had been south-east, had gone south-south-east. The lightship was now, the coxswain estimated, not more than than sixty yards from the Daunt Rock. He went to the Isolda and told her captain that the lightship was now in great danger. She was very near the rock. She was to the south-west of it. The wind was shifting. If it went a bit west, she must strike the rock.

The Rescue

The captain said that the heavy sea it was impossible for the Isolda to do anything. The coxswain asked if he should try to take the crew off. He was told to carry on. He took the life-boat round the lightship again. The seas were going right over her. She was plunging tremendously on her cable, rolling from 30 to 40 degrees, burying her starboard bow in the water and throwing her stern all over the place. She was fitted with rolling chocks, which projected over two feet from her sides, and as she rolled these threshed the water.

To anchor to windward and drop down to her was impossible, owing to her cable. The only thing was to get astern and make quick runs in on her port side, calling on her crew to jump for the life-boat as they could. The coxswain went within hailing distance and told the light’s crew what he intended to do. He must run at full speed, check for a second, and go full speed astern. In that second, the men must jump. He knew the dangers. The lightship was only 98 feet long. If he ran too far, the life-boat would go over her cable and be capsized. As he came alongside, the lightship, with her chocks threshing the water as she plunged and rolled, might crash over right on the life-boat.

There were still two men on board the light vessel. They were clinging to the rails.They seemed unable to jump. The coxswain sent some of the crew forward, at the risk of being swept overboard, with orders to seize the two men as the life-boat alongside. Then he raced in for the sixth time. The men were seized and dragged in. As the coxswain said, it was no time for “By your leave.” One of the men had his face knocked against either the fluke of the anchor or a stanchion and was badly cut. The other man’s legs were hurt. The motor mechanic was able, with iodine and bandages, to give first aid to the man whose face was cut. Shortly after the rescue, one of the men of the light vessel (the long strain on them had been tremendous) became hysterical, and two men had to hold him down to prevent anyone from being hurt or knocked overboard.

When the life-boat reached the light vessel again, about dusk, she found that the Isolda had arrived. Her captain told the coxswain that he intended to stand by all night and in the morning would try to take the lightship in tow. But the weather since four o’clock had been getting worse. At eight o’clock a big sea went over the lightship, carrying away the forward of the two red lights which are hoisted by a lightship at bow and stern to show that she is out of position. At 9.30, with the wind and sea still increasing, the the coxswain took the life-boat round the lightship’s stern, with his searchlight playing on her. In its light, he could see her crew, with there lifebelts on, and the seas breaking over them, huddled at the stern. The wind, which had been south-east, had gone south-south-east. The lightship was now, the coxswain estimated, not more than than sixty yards from the Daunt Rock. He went to the Isolda and told her captain that the lightship was now in great danger. She was very near the rock. She was to the south-west of it. The wind was shifting. If it went a bit west, she must strike the rock.

The Rescue

The captain said that the heavy sea it was impossible for the Isolda to do anything. The coxswain asked if he should try to take the crew off. He was told to carry on. He took the life-boat round the lightship again. The seas were going right over her. She was plunging tremendously on her cable, rolling from 30 to 40 degrees, burying her starboard bow in the water and throwing her stern all over the place. She was fitted with rolling chocks, which projected over two feet from her sides, and as she rolled these threshed the water.

To anchor to windward and drop down to her was impossible, owing to her cable. The only thing was to get astern and make quick runs in on her port side, calling on her crew to jump for the life-boat as they could. The coxswain went within hailing distance and told the light’s crew what he intended to do. He must run at full speed, check for a second, and go full speed astern. In that second, the men must jump. He knew the dangers. The lightship was only 98 feet long. If he ran too far, the life-boat would go over her cable and be capsized. As he came alongside, the lightship, with her chocks threshing the water as she plunged and rolled, might crash over right on the life-boat.

There were still two men on board the light vessel. They were clinging to the rails.They seemed unable to jump. The coxswain sent some of the crew forward, at the risk of being swept overboard, with orders to seize the two men as the life-boat alongside. Then he raced in for the sixth time. The men were seized and dragged in. As the coxswain said, it was no time for “By your leave.” One of the men had his face knocked against either the fluke of the anchor or a stanchion and was badly cut. The other man’s legs were hurt. The motor mechanic was able, with iodine and bandages, to give first aid to the man whose face was cut. Shortly after the rescue, one of the men of the light vessel (the long strain on them had been tremendous) became hysterical, and two men had to hold him down to prevent anyone from being hurt or knocked overboard.

Three Hours Sleep in 63 Hours

Three Hours Sleep in 63 Hours

The life-boat, after reporting to the Isolda, made for Queenstown, where she arrived at eleven on the night of the 13th February, and for the two injured men were taken to hospital. The life-boat remained at Queenstown for the night, returning next morning to Ballycotton, where she arrived at 12.45 pm. she had then been away from her station for 76 and a half hours

she had been out on service for 63 hours. She had actually been at sea for 49 hours. During the first and third days, the weather was bitterly cold, and the rain and sleet were almost continuous, and during the hole time the life-boat was taking heavy seas on board. All of her crew came back suffering from colds and salt-water burns, and the coxswain had a poisoned arm. All were completely exhausted. In the 63 hours from the time when they left Ballycotton, until the time when they brought the rescued men into Queenstown, they had only three hours sleep

The Rewards

Such is the account, as told by the honorary secretary of the station, and confirmed by the district inspector, one of the most exhausting and courageous rescues in the history of the life-boat service.

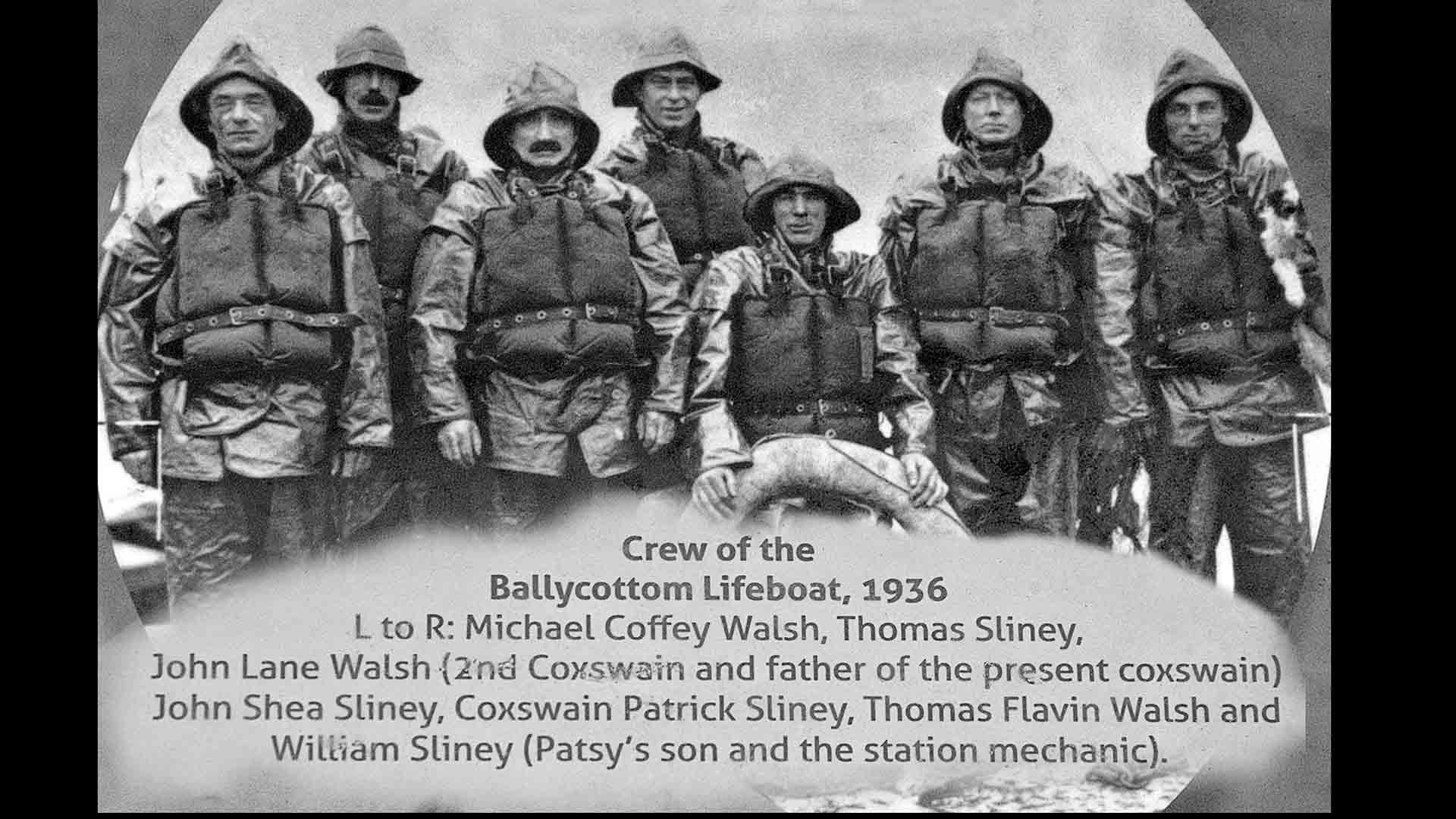

The institution has made the following awards:

Coxswain, Patrick Sliney

The Gold Medal, which is given only for conspicuous gallantry, and a copy of the vote of the medal, inscribed in vellum and framed.

Second Coxswain, John L. Walsh

The Silver Medal and a copy of the vote of the medal, inscribed in vellum and framed.

Motor Mechanic, Thomas Sliney

The life-boat, after reporting to the Isolda, made for Queenstown, where she arrived at eleven on the night of the 13th February, and for the two injured men were taken to hospital. The life-boat remained at Queenstown for the night, returning next morning to Ballycotton, where she arrived at 12.45 pm. she had then been away from her station for 76 and a half hours

she had been out on service for 63 hours. She had actually been at sea for 49 hours. During the first and third days, the weather was bitterly cold, and the rain and sleet were almost continuous, and during the hole time the life-boat was taking heavy seas on board. All of her crew came back suffering from colds and salt-water burns, and the coxswain had a poisoned arm. All were completely exhausted. In the 63 hours from the time when they left Ballycotton, until the time when they brought the rescued men into Queenstown, they had only three hours sleep

The Rewards

Such is the account, as told by the honorary secretary of the station, and confirmed by the district inspector, one of the most exhausting and courageous rescues in the history of the life-boat service.

The institution has made the following awards:

Coxswain, Patrick Sliney

The Gold Medal, which is given only for conspicuous gallantry, and a copy of the vote of the medal, inscribed in vellum and framed.

Second Coxswain, John L. Walsh

The Silver Medal and a copy of the vote of the medal, inscribed in vellum and framed.

Motor Mechanic, Thomas Sliney

Bray to Greystones Cliff Walk

Bray to Greystones Cliff Walk

Sheep’s Head

Sheep’s Head

Kilcoole to Greystones

Luke Kelly Statue

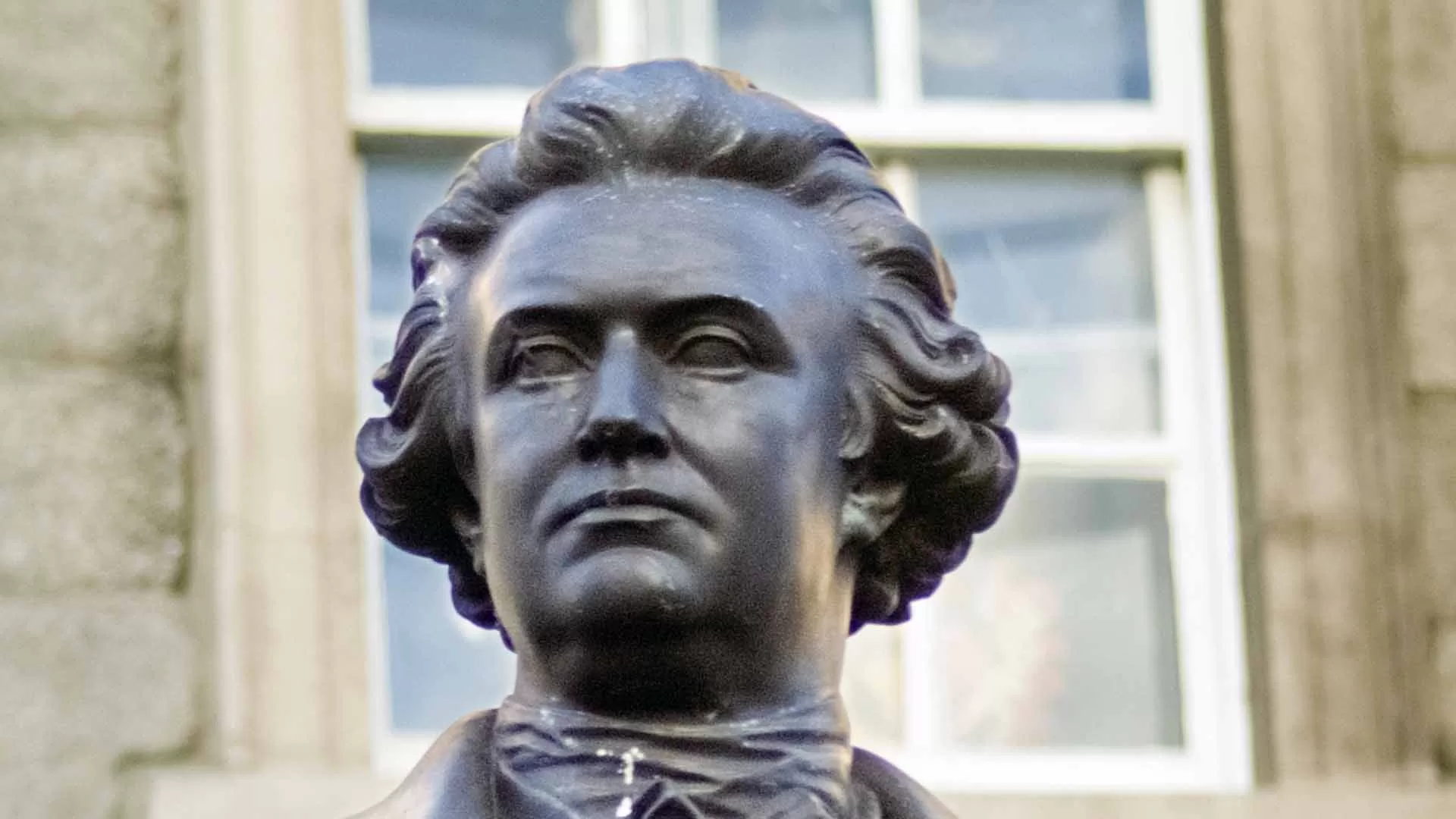

Edmund Burke Statue